Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu at a conference in Jerusalem on September 2nd.

Netanyahu unleashed

Prime Minister Netanyahu is in an unparalleled position of regional strength for an Israeli leader. The Israeli Armed Forces (IAF) are mobilised and poised; they have so far demonstrated remarkable dominance over hostile regional forces, supported by high-quality intelligence and ruthless covert action; and he has the understanding, even support, of western and Gulf powers in launching retaliation for the second wave of missiles launched at Israel by Tehran in six months. His government and the IAF have been reviewing military options with Washington, which has acknowledged this is a sovereign decision for Israel. It would not be surprising if Israeli emissaries were also having a quiet informal word in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. Beyond that, there is no one Netanyahu needs to consult, let alone negotiate with, other than within his own war cabinet. To an extraordinary extent, he is unconstrained in selecting between Iranian target sets.

Israel’s potential targets in Iran and their respective ratings in terms of advantage and likelihood

NUCLEAR SITES: some of these are dedicated to uranium processing and enrichment, others to weaponisation and delivery systems. The former have probably mostly been identified, the latter perhaps not, even by the Israelis. Some are known to be deep (50–100m) underground. To have any chance of destroying these, the IAF might have to resort to capabilities that remain subject to US consent. President Biden has declared publicly that he is opposed to any Israeli attack on nuclear sites, fearing this would spark all-out conflict and accelerate Iranian preparations for deployable nuclear weapons. The Gulf States would applaud any setback to the Iranian nuclear programme, but the Administration will be wary of the Russian response. Iranian military relations with Moscow are increasingly close and Tehran may have sought Russian assistance with nuclear weaponisation in return for Iranian supply of drones and missiles for use on the Ukrainian front.

A satellite image of a nuclear site in Isfahan, Iran

OIL FACILITIES: easy to damage, and aerial assault would not cause widespread collateral civilian casualties. Yet their widespread destruction would wreak havoc on the Iranian economy and on the living standards of ordinary Iranians, to whom Netanyahu made a remarkable direct appeal a few days ago. If the Iranians lose their own ability to process and export crude, gas and petrochemicals, that may prompt them to attack similar facilities across the Gulf, on which the west depends, and to close the Straits of Hormuz [on which more below]. This is the option most likely to spark a regional conflagration, and the one that would most worry Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. It is surprising that President Biden (whose past record on national security issues has been mixed) seems to contemplate it with equanimity, especially pre-election. The oil price, which has so far responded to events in laggardly fashion, would surge dramatically, with consequent impact on western inflation rates.

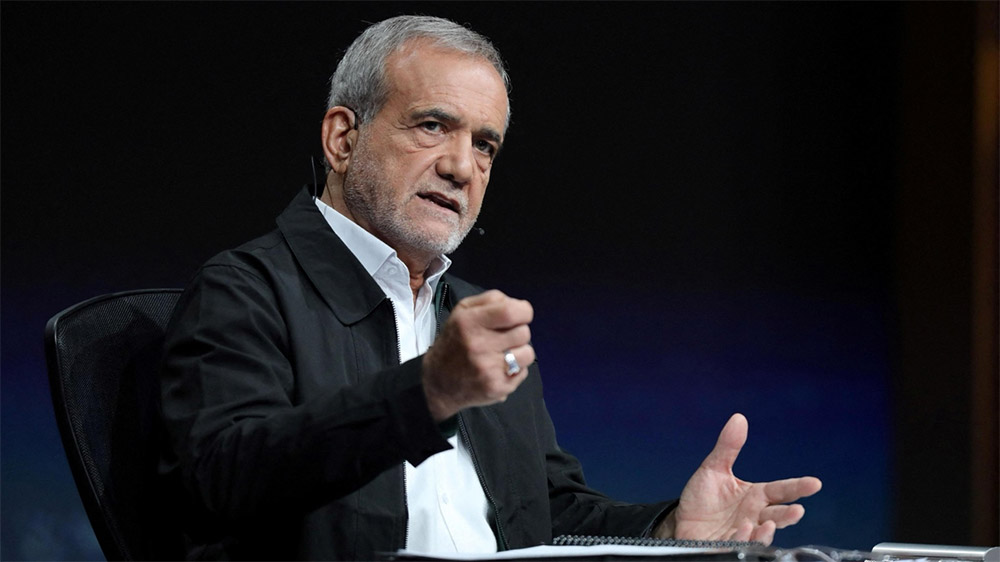

GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS AND PERSONNEL: the Israelis have shown the priority they attach to decapitating hostile groups, but it is a different order to target the leading figures of a hostile regime, especially when they have had due warning and the IAF are operating at extreme range against a large country. Tel Aviv is more likely to engage in selective targeting through assassination and sabotage, conducted by intelligence assets on the ground, as it has done in the past. The aim would be to sow dissension and confusion in Iranian official ranks after any aerial assault. There are already signs of differences of emphasis between hardline elements and Iran’s newly elected President Pezeshkian. Although potentially a reformist, the president is just as devoted to the regime’s survival, as Ayatollah Khamenei and the IRGC, but may differ in approach. The Israeli covert action campaign could be supported by cyber-attacks. Israel, a cyber superpower, will probably already be sitting on Iranian networks and so can cause havoc with the Iranian government and infrastructure. It will not wish this to damage its own technical intelligence coverage.

President of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian, secured victory with 53.7% of the vote in July

IRGC AND ASSOCIATED ORGANISATIONS: a blanket aerial assault on senior IRGC personnel, military and naval bases, and economic interests is an attractive option for Tel Aviv. These targets could include the infrastructure supporting IRGC capabilities, among them utilities, lines of communication in and out of Syria including roads, ports and IRGC carriers such as Mehran Air, all of which are used to resupply Hezbollah. Since the IRGC is the main means the Iranians use to project power in the region, such strikes would severely damage Iran’s asymmetric capabilities, in which they have invested heavily over decades. That in turn would hurt proxies reliant on IRGC, such as the Houthis, Hezbollah, and pro-Iranian Shi‘i militias in Iraq. The infliction of pain on the IRGC would be welcomed by the Iranian opposition movement, which has displayed resentment of the regime’s spending on ideologically driven adventurism abroad at the expense of investment at home. The Gulf states would also applaud any setback for the IRGC and for the Ministry of Intelligence, if included in the target set.

Whatever option the Israelis choose, the IAF will almost certainly aim to take out in a first strike Iranian air defence capabilities around sensitive nuclear, government and IRGC facilities, clearing the way for later aerial assaults. It is likely in this instance that Israel would hit missile sites, whatever else they targeted.

Then, what kind of war?

Neither the Iranians nor the Israelis are configured to fight an expeditionary war. The Iranians have relied on their proxies in the Levant, Iraq and Yemen to act as their first line of defence, as well as instrument of attack. They have also invested heavily in missile and drone capability but have a weak air force and poorly equipped land forces, which they are in no position to project. The Israelis have an effective but small army, heavily reliant on reservists, a small but well-equipped air force and a strong missile capability, as well as un-avowed, deliverable nuclear weapons. In the light of these respective capabilities, it is possible to foresee a ‘war of the cities’, in which there are further missile exchanges and a series of Israeli air attacks on Iran. A parallel war could develop in cyber space, with Iran also resorting to terrorist attacks on Israeli interests overseas (we have already seen attacks near Israeli missions in Stockholm and Copenhagen, with the IRGC reportedly borrowing from the Russian playbook in employing organised criminal elements to do their dirty work). [Argyll Assessment August 2024 – Russian campaign of sabotage and assassination targets private sector]

A key element in the balance here is Israel’s much lower tolerance for casualties and damage than Iran’s. That could lead Tel Aviv to threaten serious escalation even to the nuclear level, should Netanyahu judge that Iranian attacks jeopardised the existential interests of the Israeli state. Such a situation would surely trigger a decisive US intervention.

Gulf states looking to stay detached

For the present, there is a prevailing sense in the GCC of detachment from events in the Levant. Gulf governments have stood aside from the Israel’s war on Iran’s regional proxies. Neither Saudi Arabia nor the Emirates have any liking for these. Both governments have a deep hatred for the Muslim Brotherhood, of which Hamas is an offshoot, since it aims to take political power wherever it operates. For all their populations’ sympathy with the Palestinians and despite the dire humanitarian situation that has developed, they have stood aside as Israel has waged its campaign in Gaza. They are also pleased to see Israeli inflict critical damage on Hezbollah and on the Houthis. Their overriding aim is to remain on the sidelines, unaffected by military operations and free to pursue their economic and developmental priorities. From a technological standpoint, the relationship with Israel is important to both Saudi Arabia and the UAE, even if only the latter has formal diplomatic relations with Tel Aviv. The crisis over Gaza and Netanyahu’s refusal to discuss a two-state solution to the Palestinian issue has probably prevented Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman from following Abu Dhabi’s lead for the foreseeable future.

Crippling Hezbollah in Lebanon

The Israelis presaged their campaign against Hezbollah in Lebanon with covert action, exploiting pagers and hand-held radios they had doctored to bring down the organisation’s communications system and many in its chain of command down to the operational level. This exhibition of ruthlessness, even callousness, and technical expertise, went some way to restore their traditional reputation for being a step ahead of their enemies, after the manifest political, intelligence, security and technical failures that led to the 7th October massacres.

The remains of one of many exploded pagers that killed 32 and injured thousands on 17th September

Having killed longstanding Hezbollah leader Hasan Nasrallah, the Israelis are set on an effort to degrade Hezbollah capabilities in Lebanon, further decapitate its leadership, and delegitimise the organisation in the eyes of the Lebanese people. It has begun an operation into southern Lebanon, which it invaded in 2006, only to be fought to a standstill by Hezbollah. On that occasion the IAF were surprised by the extent of Hezbollah’s underground infrastructure and lost 46 Merkeva tanks, mainly to the Kornet anti-tank missile. They have studied their errors since, and doubtless devoted heavy intelligence resources to mapping the Hezbollah presence south of the Litani River but have already suffered casualties relatively close to their northern border. They are bound to suffer more in small unit actions.

The proclaimed objective of Israeli actions in Lebanon is to prevent Hezbollah being able to launch missile attacks into northern Israel, but, given the size and range of the Hezbollah arsenal of rockets and missiles, we may question whether this is feasible. Nor is it credible that the Israelis can eliminate Hezbollah, which is an organisation with a dominant presence from Beirut airport to the Israeli border. It is the effective government of this part of the country, as well of the Bekaa Valley to the north-east, supplying social, medical and educational service to the population, sidelining the Lebanese government and armed forces and relegating them to the status of observers. The Israelis are bombing identified Hezbollah facilities, but, since Hezbollah are the champions of a previously downtrodden Shi’i community in Lebanon, it seems unlikely they can delegitimise the movement in the eyes of its own constituency. The Lebanon government is not a viable interlocutor for the Israelis. There has not been a president for two years, the prime minister lacks a power base and the country’s economic situation is dire. This is a failed state on Israel’s borders, and Israeli bombing of the capital is compounding its misery and incapacity. If the Israelis also seek to encourage armed elements in other ethnic or religious groups to turn on Hezbollah, that will only risk a revival of civil strife in a country heavily scarred by civil war and past Israeli interventions.

Israeli strikes on the city of Tyre, Lebanon on September 23rd

It is not clear what the Israeli end-game is in Lebanon. If Netanyahu wants Hezbollah’s capitulation, then he has removed the one leader capable of delivering it. We do not know who will ultimately replace Nasrallah, but the previous leadership could be replaced by more extreme elements, which will outflank any pragmatists. The result could be resumption by Hezbollah of transnational terrorist activities. Because of Lebanese Shi‘i diaspora communities in West Africa and South America, as well as the movement’s longstanding organised criminal links through its drug running, Hezbollah has had a long reach in the past. The devastating suicide bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires in March 1992 was a response to the killing of the previous Hezbollah leader in February that year. In July 1994, this was followed by another, equally destructive, truck bombing of a Jewish community centre there.

Continuing campaign in Gaza without an end-game

Netanyahu is maintaining the military campaign in Gaza with the aim of freeing the remaining hostages but also with the proclaimed objective of eradicating Hamas, a goal that is arguably as unachievable as that of suppressing Hezbollah. Supreme tactician but no strategist, he has not explained what the Israeli government’s end-game is in Gaza. So the campaign goes on in a strategic vacuum. This is disturbing for western governments, faced by a terrible humanitarian situation, the potential for a Palestinian uprising in the West Bank, and growing polarisation among western electorates over the fate of the Palestinians. Multi-front campaigning is straining the Israeli economy, especially because of IAF reliance on reservists.

Tehran and the chokepoint at Hormuz

40 percent of the world’s seaborne-traded crude oil passes through 25-mile gap at Hormuz every day. It is also vital for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) deliveries to Europe. This makes it one of the world’s most strategically important chokepoints, which Tehran has historically threatened in the past to close in response to foreign pressure. It could certainly choose to do so in response to a major Israeli attack on Iranian territory. Short of that, it could have IRGC boats, helicopters and drones harry and harass international shipping. None of this would be welcome to Beijing, which may weigh in with Tehran on a pre-emptive basis.

Iran is as dependent as its neighbours on the Straits being open to ensure its oil and gas exports reached the international market, but the regime has made a concerted effort to develop redundancy measures by diversifying its oil export routes and other infrastructure. The Goureh-Jask pipeline takes oil to a refinery and terminal at Jask, located on the Gulf of Oman, while the Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline offers an alternative, though vulnerable, route for Iranian oil. It is doubtful these redundancy measures would be effective, if Tehran sought to allow only its own tankers through the Straits, since it is probable the US would blockade Iranian exports.

As we have previously noted in an assessment [See Argyll Assessment February 2024], the effect of closure of the Straits on the global oil market would depend on: the extent of disruption; the actual and perceived length of disruption; the market tightness at time; the inclusion of the particular disruption in any risk premium in the price; the cause of disruption; the response from OPEC and associated producers (especially Saudi Arabia), and from International Energy Agency (IEA) member countries; and the type of crude affected.